Turning Livestock Waste into Renewable Energy with Micro-AD Innovation

Rudimentary anaerobic digesters are part of life in many developing countries. Most villages have some sort of system where microbes turn organic waste into biogas for energy, while producing fertiliser to return to the land.

Although the technology is widely recognised as a climate-positive way to produce renewable energy, in developed countries AD plants tend to be installed on an industrial scale. The potential of AD at a much smaller scale as a way to help farmers reduce their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions has been largely overlooked. That’s all about to change as a Hertfordshire-based agri-tech company brings micro-biodigesters to market.

From concept to product

EcoNomad is the brainchild of business entrepreneur Dr Ilan Adler who has been working in the biogas sector for over 20 years. In the early 2000s, he founded the International Renewable Resources Institute, a charitable NGO working with rural communities in Mexico to solve water issues. It was here that he first came across a very basic anaerobic digester that was being used by a lady farmer to process the manure from her three pigs and produce biogas for cooking instead of using firewood.

“I saw this and realised it could be a gamechanger and had the potential to transform the lives of smallholder farmers and their communities. Not having enough fuel for cooking is a worldwide problem, so we added AD to the NGOs remit and began to build our own,” he says.

Demand quickly grew beyond the level a charity could manage, so the rollout of small-scale biogas systems transferred to social enterprise with the founding of Sistema.bio in 2008. The company has since installed over 100,000 biogas units under the leadership of entrepreneur Alex Eaton.

But it wasn’t until returning to University College London (UCL) in 2014 that the potential for micro-AD systems in the UK dawned on Dr Adler. Following the realisation, two systems were installed as student projects, winning a sustainability award. In 2018 he was awarded a fellowship from the Royal Academy of Engineering, freeing up time and providing funding for the genesis of a business to commercialise the technology, EcoNomad. Soon after, the new company filed its first patent to protect its intellectual property.

The following year the company received an AgRIA ERDF grant to develop the first protype systems. At around the same time the new SHAKE Climate Change accelerator was launched – a consortium-based programme led by Rothamsted Research that brings together experts from Rothamsted Research, Cranfield University, University College London and the University of Hertfordshire. SHAKE awards funding and mentorship to companies that provide climate positive solutions in agriculture and food production and EcoNomad was one of four companies successful in its first round of funding in 2020.

Mitigating climate change

Agriculture is a sector that significantly contributes to GHG emissions. Much of this comes from the storage and handling of animal manures. In the UK and EU, 1.4 billion tonnes of livestock manure is produced annually, equivalent to 600 million tonnes of CO2 as less than 10% is currently being processed to reduce the GHG emissions associated with it.

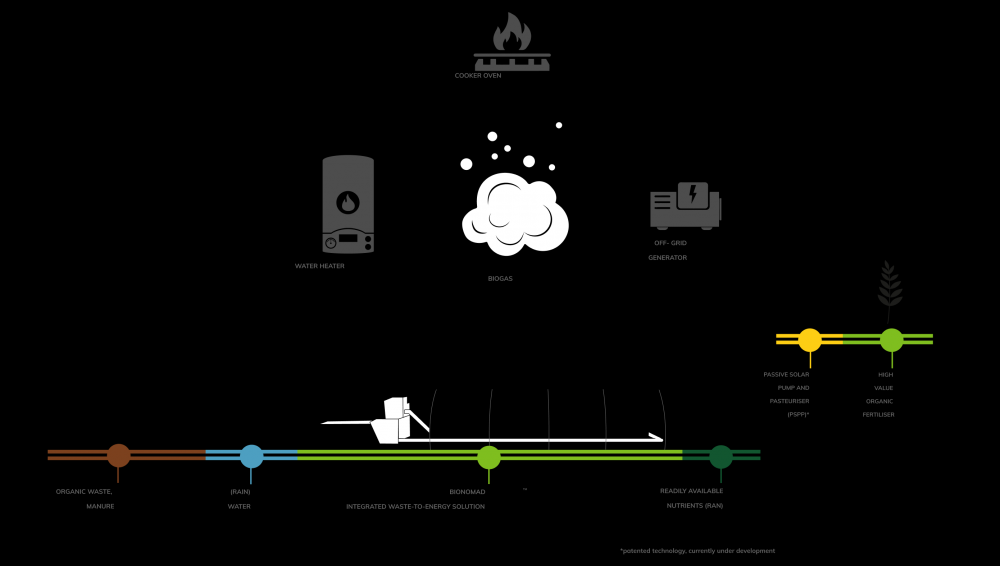

SHAKE saw the potential to do so much more and that EcoNomad’s technology offers a solution because its BioNomad micro-digesters are suitable for the smaller farms that are typical (90-94%) in the livestock sector. For the first time this makes anaerobic digestion accessible to a huge cohort of farmers in cooler climates to process livestock waste, complete the nutrient circle and reduce GHG emissions.

According to Dr Adler, the benefits of anaerobic digestion are threefold – reducing GHG emissions, providing a substitute for fossil fuels and generating organic fertiliser.

During the process, microorganisms break down organic matter and produce biogas, a mixture of methane (CH4) and carbon dioxide (CO2). When biogas is burned as fuel, CO2 is released into the atmosphere.

“The end result is that methane, a greenhouse gas 22 times more potent than carbon dioxide, is transformed into carbon dioxide when biogas is used for heating, electricity generation and as a vehicle fuel, replacing fossil fuels. The AD process also produces digestate that can be returned to the land as fertiliser, reducing the need for synthetic nitrogen fertilisers and the emissions associated with its production and application,” he explains.

So, to what extent can micro-AD help mitigate climate change? Under its SHAKE mentorship, the company commissioned a graduate researcher from the University of Bath to quantify the impact of its technology using predictive modelling under IPCC guidelines.

“These show that the wider climate change impact from our solution is a considerable reduction in methane and nitrous oxide emissions (>30%) from manure. A typical smallholder farm of about 50 cows will save around 0.5 million tonnes of CO2-eq per year,” says Dr Adler.

The company is now building a real-time model using its installations so that the predictive model can be validated, he adds.

Catapulting growth

EcoNomad has recently received a major grant of £535,000 from the Energy Entrepreneur Fund, which requires 20% match funding from investors. The cash injection is being used to support pilot installations and trials prior to a full commercial rollout of BioNomad digesters in early 2025.

Dr Adler believes match funding is an important element of catapult programmes and acts as a reality check because companies must offer a viable commercial opportunity for investors to be willing to put in the additional finance.

“Match funding makes a company get out and raise funds and investors feel more comfortable putting money in as the government is backing up their investment with the other 80% of the finance.”

Government could do more to enable uptake of the technology, he adds. “Reintroducing or improving feed-in tariffs/incentives to provide long-term revenue for renewable heat/gas production would be a step forward.

“Currently countries in Europe have much more generous incentives available to them so there’s potential to model support programmes after successful examples in countries like Germany that grew renewable industries with generous upfront incentives and subsidies for solar, biogas, etc.,” he suggests.

The company has identified the European Union as its biggest potential market and has recently visited farms in the Netherlands and is preparing a proposal for a pilot project in France. EcoNomad also has three smaller pilot projects underway in Rwanda, Malawi, and Uganda that were supported by Innovate UK grants.

“Feedback from these projects will help us understand growth opportunities in Africa,” adds Dr Adler. “The payback time for systems in places like Uganda is much faster due to greater energy needs and higher costs of alternatives like bottled gas for off-grid communities. International projects also allow us to test our technology in diverse conditions and markets.

Further options that Dr Adler believes would help government better support agri-tech innovation and farmers’ transition to a more circular economy include:

- Increased incentives for carbon reductions, such as through more robust carbon credit programmes

- Continuing and potentially increasing the benefits available under the Seed Enterprise Investment Scheme (SEIS) to incentivise early-stage investment in renewable startups

- Provision of grants that cover a significant portion (e.g. 50%) of capital costs for small farm renewable projects up to a certain value

“EcoNomad was supported by two rounds of SEIS funding, and we still have some left. It’s a brilliant incentive. It’s risky for investors to go into any company during its early stages so this scheme is crucial and the biggest error any government could make is to remove it.

“The Enterprise Investment Scheme (EIS) is less generous but it’s a good follow on. I’m a strong advocate of both government schemes because they pay off. The companies it invests in progress and eventually hire more people and pay more taxes,” he says.

Bucking the trend

The majority of startup companies cease trading within the first five years, so how does Dr Adler account for EcoNomad’s resilience? “It’s involved tremendous stress and sleepless nights as an early-stage company. Finding the right team has been challenging and sticking with the business through difficulties such as COVID-19 has required an immense passion for improving small-scale sustainable energy solutions and working with rural communities.”

He also emphasises the importance of flexibility, adaptability, and being able to pivot the business model in response to changing external conditions, like Brexit or new government programmes, in order to ensure the company's survival through unpredictable challenges.

EcoNomad still maintains close links to the SHAKE mentoring network and it’s this that sets the programme apart from other accelerators, says Dr Adler. “The SHAKE programme is valuable because it offers business mentoring support that’s specifically tailored to agri-tech, which was new to me and helped us with early pitches. But most importantly, it also provided a link with Rothamsted Research – where the company is now based – whose networks have been really useful for collaboration and testing.

“We’re preparing to launch another investment round and will seek support from the SHAKE network to help us secure this,” he concludes.